Vectors #

Vectors are a simple data structure that contain a set of floats - numbers. They are incredibly useful!

After looking through this high-level-overview page, I recommend reading this page on Vectors in the Unity manual.

Vector Overview #

Types of Vectors in Unity #

In Unity, we have a number of different ‘vector’ data structures:

The number refers to the number of floats that the vector contains. The floats are named in using standard mathematical letters you are likely familiar with from middle school algebra: X, Y, Z, and W. In that order.

Vector2’s have an x and a y property.

Vector3’s have an x, a y, and a z.

Order of Units #

We always use the same order: x then y then z. So if one says, out loud, that an object is at position “twelve thirteen zero”, we know it has a position vector with x:12, y:13, z:0, often written in parenthesis and separated by commas: (12,13,0). This nomenclature comes from algebra, and should feel familiar.

What Vectors Are #

Vectors are containers for a set of numbers, and a bunch of functions for manipulating and working with these sets of numbers. In mathematics, we might use the idea of a “pair” or “tuple” for such containers.

What Vectors Represent #

When I say that vectors are “just containers for a set of numbers”, this definition probably falls a little flat. We often speak about vectors in the context that we use them, and we use vectors in lots of different ways. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, just look at the Wikipedia Disambiguation Page for Vectors. When we speak about vectors, we are probably talking about them in terms of “Euclidean Vectors”, so give that wikipedia page a skim too.

Some of the things that vectors commonly represent in Unity:

- A position in a cartesian coordinate system

- A position on a grid (also see: Vector2Int for this use case)

- A direction

- A force

- A change in position/direction/force

- An acceleration of (a change in the change in position/direction/force)

- An orientation (as “Euler angles”, each property is angles in degrees around axes, executed in a specific order)

- A rotation (change in orientation)

- A torque (force applied to rotation)

- A Scale

- 2D axes (e.g.: angle of a joystick controller)

- Surface Normals (often stored for a model as a normal map, not as vectors in C#)

So vectors are pretty useful! Lets think about some common uses a bit more particularly.

Vectors Can Represent Anything #

If I want to use a Vector3 for “playerStats” and let the x be the players health, y be the players mana, and z be the players charge-o-meter, then sure. Why not?

Well, because that’s silly. If you want to store all these as 1 variable, you can make your own data structure to represent it. Your code data structures should represent what your data is. Don’t just use a vector because it’s there, and convenient. We want the functions that vectors come with to be useful to us. What would it mean to “normalize” a health/mana/charge-o-meter vector? It’s an incoherent thought.

But Vectors, as a data structure, are just a set of floats. They can represent whatever you want them to represent. We commonly use them in contexts that aren’t just 3 related values, but where vector-based math is useful. This includes forces, directions, and positions, the most common use cases for Vectors.

Vectors for Position, Rotation, and Scale #

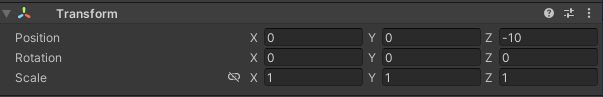

An objects position, rotation, and scale is called it’s transform. We edit all of these properties via vectors inside of the transform component.

The position is a number of units along each axis of the cartesian coordinate system. Its nice to think or our scenes as cartesian coordinate systems. The gameObjects are some number of units away from that gameObject’s parent position, or the origin of the scene).

The rotation is stored internally as a Quaternion (a different data structure that is also just 4 numbers) for annoying math and performance reasons, but quaternions are annoying to work with, so we often edit rotations via Euler angles: positive-or-negative degree’s around each axis.

The scale is a multiplier along each axis from some default scale. A scale of (0,0,0) is infinitely small, and will make almost every object invisible. A scale of (1,1,1) is the default scale of that object. For most objects, like default cubes, this will end up taking up about 1 square (or cubic) unit of the world-grid, but the reality of that entirely depends on your project and your assets. It’s all relative.

Vectors for Speed #

Each value is the speed along that axis. We just need to decide on the units.

Moving past algebra, Vectors can be used to determine speed. What units we use depends on their context. If speed is position-per-time (e.g.: meters per second), we can assume that the position unit is the same as our world space; it’s the time unit we have to decide on.

It’s common to use seconds. This is pretty easy to work with, we just have to convert it from per-second to per-frame before actually moving an object on a specific frame (inside of an Update Loop). We do this by multiplying a per-second unity by Time.deltaTime, and we usually do this at the time of applying the value (ie: use deltaTime inside of the updateLoop, not elsewhere).

Vectors for Direction #

Vectors for position assume are usually relative to the origin of the scene (“world”). Direction disregards this notion entirely. A direction vector assumes that our object is the position (0,0,0) of the vector. Any values will “draw an arrow” away from the object - this is now a direction. We can apply it to any object anywhere. (1,0,0) is a direction pointing along the positive x axis. (0.5,0,0) is ALSO a direction pointing along the positive x axis.

It’s good practice to “normalize” direction - make the length of the vector equal to 1. This helps us when using the vector for reasons that will be apparent as a bug when you forget to normalize it.

We call a vector with the magnitude of 1 a “Unit vector”.

Similarly, with rotations, Vectors may represent an axis that something rotates around.

Vectors for Force #

A force is a direction and a magnitude. Well, what if we started with a direction, and use the vector’s length to represent the magnitude of the force? Done. Brilliant.

Vectors for Rotation #

We generally want to avoid doing this for reasons that will be discussed later. Euler angles are nice for humans to edit, but not so nice for computers to work with. We are programming, so we want to be nice to the computers (so to speak) to help prevent bugs and avoid gimbal lock.

Common Mistakes with Vectors #

Losing Context #

The most common way to mess up a vector is to lose context of what the vector is relative to, or forget it’s unit. Is this speed a unit per second or unit per time? Is the rotation in degrees or radians? Is this a direction or a force? Is this position relative to the parent, or relative to the world?

Which direction is up again? Y, right?

It can be easy to forget this, and then one ends up applying the wrong operation to it.

When you create a vector, consider adding a comment that describes the vector and reminds you of its context and units.

Vector2 piecePos;//Chess Pieces position on the chess grid. 0,0 is always A1, bottom left for white.

Vector2 playerInput;//Input axis. From arrow keys or joystick, x and y should be in the -1 to 1 range and 0 means no input.

Vector3 aimDirection;//World direction the player is aiming in.Casting A Vector Incorrectly #

You should know if you want to use a Vector2 or a Vector3, because converting between the two implies a loss or gain of data. If you accidentally convert (“cast”) your vector from the Vector3 data type into a Vector2 data type, the “z” value will get lost. Going the other way, a default value of “0” will be provided for the z component.

Mistaking Transform shorthands and Vector3 shorthands #

Vector3.up is an always-readable vector that represents (0,1,0). Vector3 upDir = Vector3.up is much easier to type and read than Vector3 upDir = new Vector3(0,1,0);.

Transform has similar shorthand vectors. They are not relative to the world, but to the current orientation of that transform. transform.up may not be equal to Vector3.up. Vector3.up will be up in world space, transform.up will be up relative to that transform.

These shorthands are very useful, but it’s all too easy to type the wrong one, and then be annoyed when the player always shoots their bullets towards the top of the screen instead of the direction they are facing.

Basics of Vector Math #

Now that we understand how vectors are used, you can go back to the VectorCookbook page in the Unity Manual to review vector math.

Remember, you shouldn’t have to do the vector math. You just need to understand it so you can write the code expressions correctly.

Normalizing #

In Unity, there are two functions to normalize a vector. One will normalize the vector (Normalize()). The other will give you the normalized vector without changing the values of the original vector (.normalized).

Vector2 someVector;

someVector.Normalize();//changes someVector to now be normalized.

someVector.normalized;//returns a new vector that is the normalized vector of someVector. Does not modify someVEctor.Dot Product #

For what it’s worth, this is a good video explaining the dot product.

Vocabulary #

- Normalize: The process to make the vector have a length of 1.

- Magnitude: A Vectors length - distance away from (0,0,0).

- Unit Vector: A vector that has a length of 1.

- Components: Another term for the numbers that make up a vector. “The x component” of a vector.

Other Resources #

This video is in Python, not C#, but helpfully gets into the math of unit vectors and explains things well:

This video is useful introduction to understanding how vectors get applied to 2D motion in the context of physics.